Duh

Aline Cateux

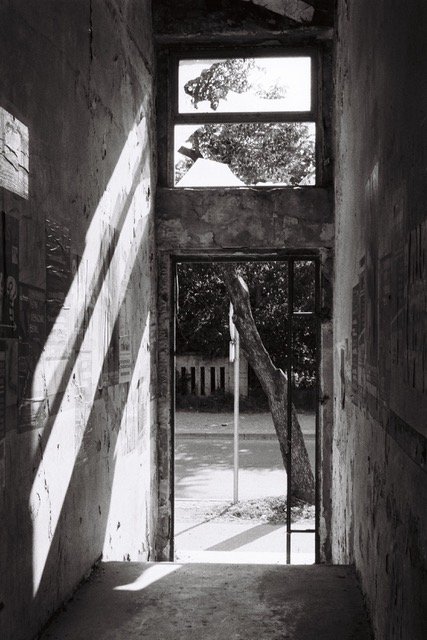

Photo: Aline Cateux, Abrašević-Mostar, July 2003.

She was materializing more than appearing. Her silhouette unnerved me. Sometimes, she popped up out of nowhere, asking for a light by pointing at her cigarette. I don’t recall ever hearing her voice. Duh, that’s what she was called. One of the first words I learnt in language that was then refered to as Serbo-Croatian, a ghost. Duh was a lady in her late fifties, maybe a bit older. It was hard to tell because her face was covered in layers of make-up, like a mask of sorts. Big black eyes and red lipstick spilling over her lips. She wore long gloves and added black plastic to her outfits that made her look like a character from one of Egon Schiele’s paintings.

She was floating down Šantićeva area of Mostar in the early 2000s. The former frontline was an apocalyptical landscape with nothing vertical left standing. She was there, in the middle of the ruins, chain smoking and peering at the passersby, who in turn, tried to escape her gaze. I frequented that part of the city because Abrašević, the cultural center our collective was fighting to reopen, was located at Šantićeva 25.

I was always anxious to see Duh, to be surprised by her sudden appearance. As far as I could tell, people in Mostar were not happy to see her either. She didn’t seem to know anyone, or maybe people who used to know her avoided her. Some of my acquaintances were agitated by her presence. What does she want? Why is she here? They waved her away, as if she were a dog, as if seeing her evoked something embarrassing, even unbearable.

At some point, I asked my local friends if anyone knew here or what had happened to her. She seemed like a victim of something to me. My activist friends always told more or less the same story:

She had been the most beautiful woman in the city, a femme fatale. She had lived a crazy love story that destroyed her. She had been arrested during the war and raped. She had been arrested by the man she had loved. She had been tortured by that same man. She had been betrayed.

All these versions fed what I felt. Duh, in her own manner incarnated the pain and the violence survived by so many in Mostar, which is why people didn’t like to see her. She was a reminder, a little stone in people’s shoes that caused them to stumble on their daily commute through ruins. Duh was a sting, the walking scar among walking scars that had chosen to express her pain through a kind of theatrical persona and the devastation of the city, her stage.

I don’t recall when she disappeared. Nobody seemed to know what happened to her. The memory of Duh came back to me a couple of years ago as I was writing a text about the reading of The Pathseeker by Imre Kertész that I had discovered in Mostar in the years Duh was haunting me. She was buried so deep in my memory that I wondered if she’d actually been a ghost.

Asking my teammates from Abrašević if they remembered her—we witnessed her apparitions together almost twenty five years ago—I sensed that no one still wished to talk about her. I asked on social media if anyone remembered her or knew something about her. It seemed that people didn’t like to see her then and didn’t like to remember her now. While gathering information for this text, a friend of mine told me: “She was not what you think she was. She was evil. I just recently found out that she was physically violent to her family.”

That revelation left me baffled. I didn’t ask for more details. Suddenly I realized how much I had cemented Duh into a fictional character, a romantic stereotype of the victim who could not be anything else. I have been so oblivious of everything I had learnt about the many layers of one’s identity.

Even ghosts are complex beings.