My Grandfather is a Cadaver I Dissect from Afar

Natalie Kikić

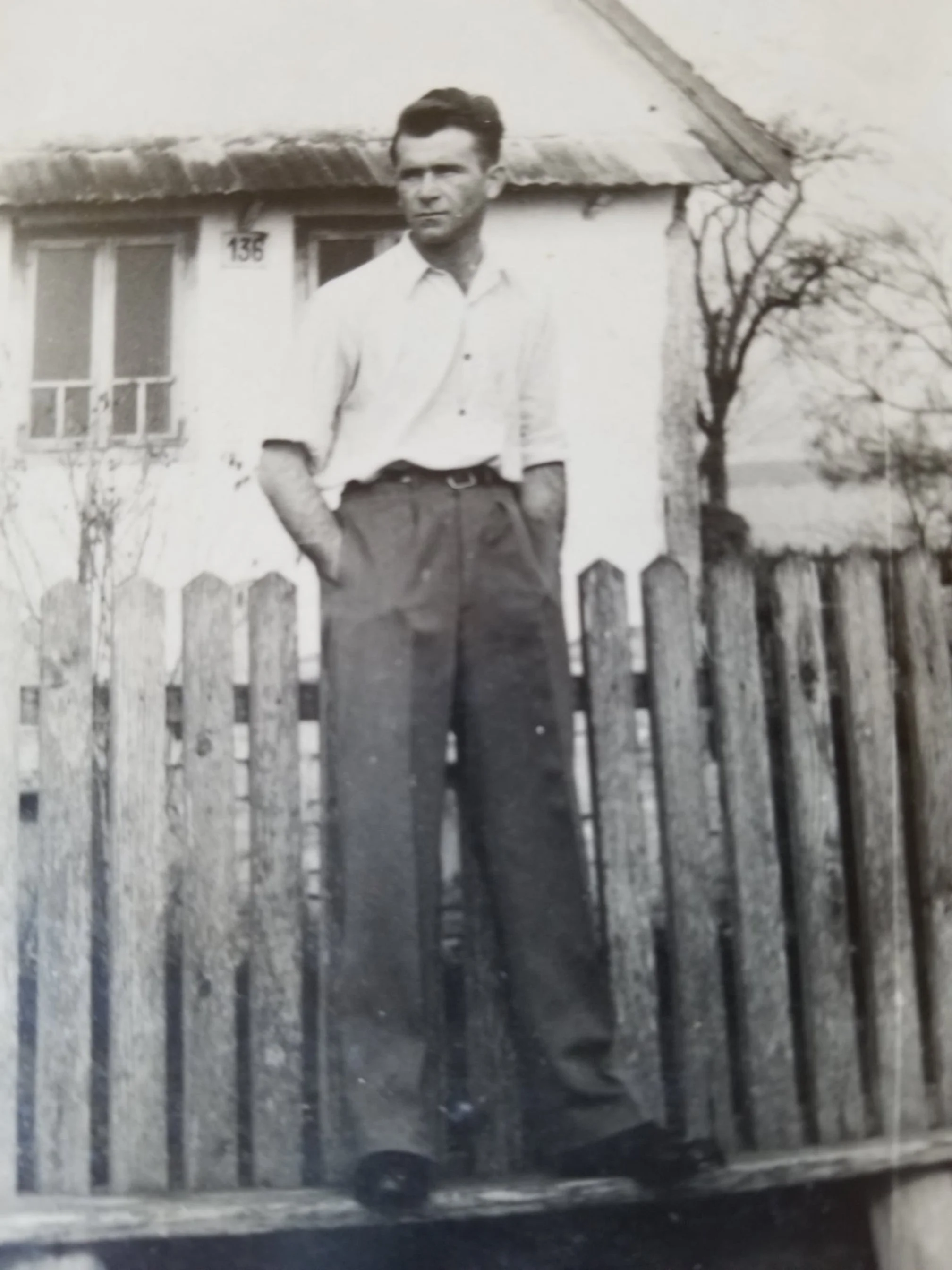

My grandfather is a body in a horse-drawn carriage, trudging through the streets of Pristina. When you see the black horses, you know someone died, my mother tells me. My grandfather’s face stares from an osmrtnica nailed to a tree, his life story scrawled in Cyrillic. His name is Josip, Jozo among friends. Not to me. I only knew him through stories, like this one. Deda, grandfather, ghost, the words are all the same.

The procession of the dear dead will begin soon, the obituary says. It leaves from Blok 5 at 14:00, heading to Pristina Cemetery. We, the mourners, must follow behind. It is tradition. Come, my mother says. It has already begun.

As we walk, pieces of my grandfather’s life tumble out. I collect them greedily; their sharp edges shine in the dark.

My grandfather is a musician who studied music in Prague. He enjoys classical music. Alcohol more. He is no Beethoven, but he plays orchestra for Radio Pristina. He loses the job, gets a new one. Loses that one too. He shakes when he needs a drink. He shakes my hand firmly—no, gives me a kiss on both cheeks. He is family, after all. He plays tuba in the Royal Yugoslav Army. Sometimes he plays at home. During World War II, the army sides with the Ustaše. Though he is a soldier, he doesn’t agree. He is a former altar boy. He is a Croat but not a nationalist. He gets along with everyone. When he’s drunk, he yells about the terrors he witnessed. Yells about bodies with eyes plucked out, floating down the river Sava. When the war ends, my grandfather disappears. He is presumed dead, well-versed in dying already. It drives his mother mad. He is her only son. She goes to the Sava too, submerges herself in its depths. She survives. He resurfaces three years later, haunted. Ghost or man, no one is sure.

My grandfather irons his shirt to collect his pension, then spends it all in one day. He passes out in the dirt as kids steal his money. He is a crumpled pile of clothes as they heave him into the neighbor’s cart. My grandfather shows up at my mother’s school, yelling to come see the doll he bought her. Bambina is the doll’s name. He makes Bambina a wooden bed. He chases my grandmother through the yard with an axe. It takes both children to pull him off her.

My grandfather is a ghost dressed all in white in my mother’s dream. A premonition. On the day he dies, he is bleeding everywhere. He was supposed to stop drinking after the surgery on his legs. He was supposed to do a lot of things. It was a relief, my mother said. The house reeked of rakija.

My grandfather is a cautionary tale, hovering over me every time I have a drink. He is a cadaver I dissect from afar, dead before I was even born. And so I study his pieces, his heart and liver, trying to understand the man he was. The grandfather he might have been. I search for parts to keep, but only the worst of him remains.

On a rainy night, so my mother says, he bangs on the neighbor’s door to let him inside. It is the wrong house, but there’s no telling him that. He doesn’t recognize my mother, too drunk to know family from stranger.

He must be carried. There is no horse and cart. It is late, but there is a construction worker smoking nearby. He takes the shoulders. My mother takes the legs. He is dead weight between them. They lumber up three flights of stairs. They lay him in the bathtub, exhausted. A ghost should not be so heavy.

It is just in time. The procession has ended. We have arrived at the cemetery. I know what to do, thanks to the stories I’ve collected.

I take the shoulders. My mother takes the legs. I falter beneath his weight. A ghost should not be so heavy.

We lay him down. We lay him down in his grave. He needs to rest, but there’s no telling he’ll obey.